oz perkins' grief & generational trauma trilogy

pop a perk and confront the real demon (the inevitability of death)

I think the apple's rotten right to the core from all the things passed down

from all the apples coming before. I split the apple down symmetrical lines, and what I find is kinda scary!

Recently, I watched a video essay about how Wes Anderson’s three latest films — The French Dispatch, Asteroid City, and The Phoenician Scheme — form something of a thematic triptych for the director: his Existential Crisis Trilogy.

It’s a great watch, and it left me even more convinced that I need to rewatch Asteroid City ASAP. But it also got me thinking about another director with a lot in common with Wes. You know him, folks. Say it with me… OZ PERKINS!

…ok, so they might not have a lot in common in terms of directorial style. But Oz does have his own trilogy of films that revolve around common themes: grief, generational trauma, and the interweaving of the two.

What I’m saying here is if Wes Anderson’s favorite song is “Life on Mars?” by David Bowie, Oz Perkins’ favorite song is “Apple” by Charli XCX. Walk with me.

This post contains spoilers for The Blackcoat’s Daughter, Longlegs, and The Monkey.

As the Blackcoat’s Daughter of a Father…

Devoted GATM readers will recall that I am the daughter of a father of a daughter. So, it’s fitting that I enjoyed Oz Perkins’ debut feature, The Blackcoat’s Daughter, as much as I did! My dear friend Sam showed it to me about a month before Longlegs came out, and although I enjoyed it at the time, I now see it as a crucial jumping-off point to understand and appreciate Oz’s later work.

The Blackcoat’s Daughter follows three timelines and, respectively, three young women: Rose (Lucy Boynton), Kat (an incredible Kiernan Shipka), and Joan (Emma Roberts). Rose and Kat are spending a bleak winter break at their Catholic boarding school (Barton men represent!) and Rose is worried that she might be pregnant. Kat’s dealing with her own problems: she’s having premonitions of her parents’ death, and she shows signs of being possessed. Meanwhile, Joan escapes from a mental institution and hitches a ride with a kindly older couple.

As it turns out, Kat isn’t just possessed; she’s willingly communing with a demon. (Via payphone, as one does.) Following its instructions, she murders Rose and two of the school’s nuns. We last see young Kat in a mental institution, strapped to a bed as a priest performs an exorcism. Although horrifying, the scene is also emotional — even tragic. “Don’t go,” Kat begs the demon, her only companion after her parents’ death.

Afterward, what’s been heavily hinted throughout the film is confirmed: “Joan” is actually an older Kat. The couple giving her a ride are Rose’s parents, on their way to the school to pay tribute on the anniversary of her death. Kat murders them and attempts to summon the demon — but it doesn’t work. The movie ends with her utterly alone, sobbing in the middle of the frozen road.

With its slow-burn pace and very grim ending, it’s no surprise that The Blackcoat’s Daughter is polarizing. But if you know Oz Perkins’ history — besides playing David Kidney in Legally Blonde — I think it’s impossible not to at least appreciate the movie. Both of Oz’s parents died in tragic and traumatic ways when he was quite young. His father, actor and horror icon Anthony Perkins, died of AIDS when Oz was 18. His mother, actress Berry Berenson, was a victim of the September 11 attacks; Oz was 27.

It’s not surprising that someone who lost both of their parents before they turned 30 would make art to express and explore grief. The Blackcoat’s Daughter takes a simple, dark approach to this topic by centering a lonely girl with sympathy for — and from — the devil.

What is surprising to me is that anyone would fail to see how Oz Perkins’ newer films continue to explore this theme of grief — just with an extra sprinkling of generational trauma on top.

Camp? In My Serial Killer Thriller?

The first time I saw Longlegs, I’ll admit I was a little put off. The movie’s NEON-led marketing campaign was incredible, producing viral moment after viral moment, and it seemed to promise a psychological crime thriller à la The Silence of the Lambs. But as “Bang a Gong (Get It On)” by T. Rex played over the film’s closing credits, I felt myself getting annoyed.

Evil dolls with magic metal balls in their heads? Nic Cage in a full face of Botched-esque prosthetics and makeup? Camp? This was not the serial killer thriller I was promised.

The second time I watched Longlegs, this time in glorious 35mm at my local independent theater and free from the burden of my own expectations, it clicked for me.

Longlegs follows FBI agent Lee Harker (scream queen and Joe Keery terrorizer Maika Monroe) as she investigates a series of murder-suicides tied to a figure known as Longlegs (Nicolas Cage). Lee’s investigation leads her down a somewhat convoluted trail of clues, which I’ll spare you from for the sake of brevity. What’s important is that she discovers Longlegs has been manipulating her mother, Ruth (Alicia Witt), for years, threatening to kill Lee if Ruth doesn’t serve as his accomplice.

Similar to The Blackcoat’s Daughter, there’s a satanic element to Longlegs in that the titular character serves “the man downstairs.” This has a double meaning; Longlegs works for Satan, but he’s also been hiding out in the Harker’s basement for years. But while The Blackcoat’s Daughter centers a troubled young girl who turns to the devil when she loses her parents, Longlegs features a parent who turns to the devil to avoid losing her child.

In an interview with People, Oz Perkins shared that the driving inspiration behind Longlegs was his mother’s attempts to shield him and his brother from the truth about their father’s sexuality. “Our parents are the most responsible for what works in us and what doesn't work in us,” Oz told People. “We're carrying them around.”

This idea of inheriting generational narratives forms the core of Longlegs. At the end of the day, many of us are willing — even happy — to believe the stories that our parents tell us, whether or not they’re true. It’s why the movie is twisted and fantastical, bordering on camp; it’s a dramatic exaggeration of a very real experience that Oz had, and that many other people have.

As Oz put it, “Your mother can protect you from a truth that she thinks is unsavory. And then you just build out a crazy movie around that.” In the case of Longlegs, Lee’s religious mother was willing to commit extreme acts of violence and serve literal Satan in order to protect her daughter from the truth. And if you think that’s absurd, Oz’s latest movie combines the themes of the previous two movies — grief and generational trauma — to reach even greater heights.

Theo James, We Will Get You That White Boy of the Year Award!

It’s late June, and The Monkey is still sitting pretty in the number-two slot on my list of favorite movies this year. (And it was in first place before The Phoenician Scheme supplanted it!)

Opinions on The Monkey are fairly well distributed; Letterboxd shows an almost-perfect bell curve with an average rating of 2.7 stars. From my reading, people were quite lukewarm on it when it came out, and it doesn’t seem to have made a big impact on the broader film conversation this year.

This is insane to me. In fact, my love for The Monkey is basically the whole reason I decided to write this post. (That, and I really wanted to use the “off tha perk” joke.)

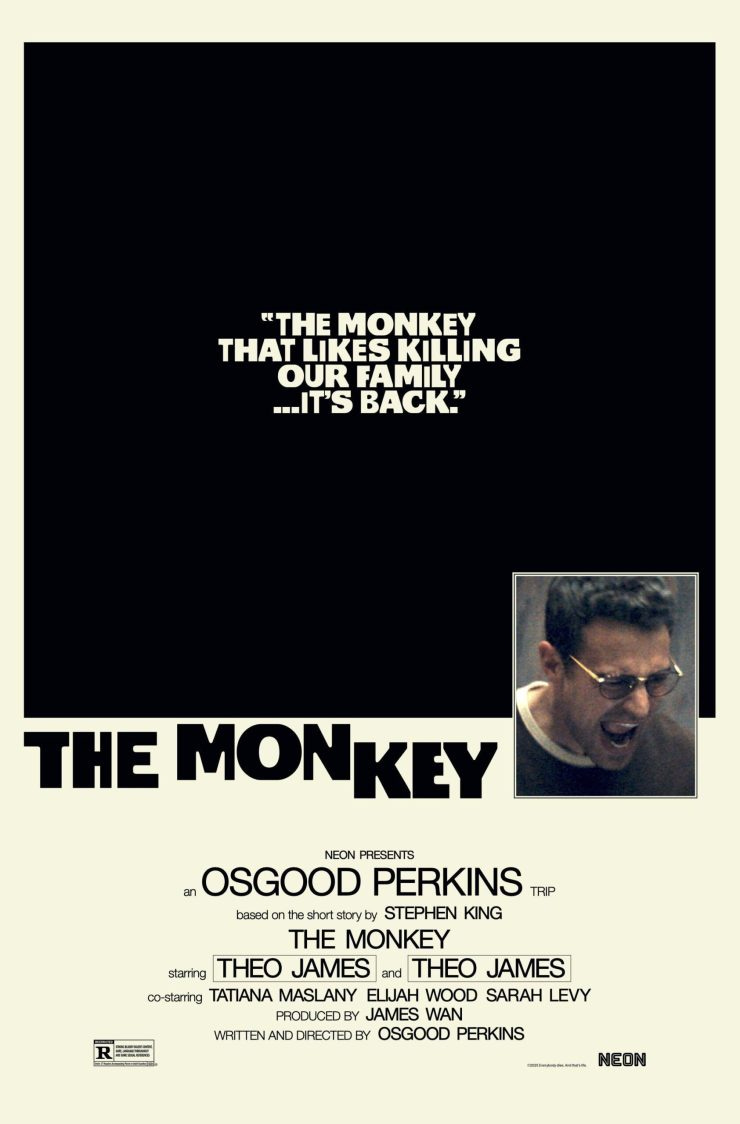

Besides being a total blast — and having a sick poster that parodies Paul Schrader’s Hardcore — The Monkey serves as the perfect culmination of Oz Perkins’ exploration of grief and generational trauma.

It follows twin brothers, Hal and Bill (both played by Theo James), and the cursed toy monkey that causes the people around them to die random, violent deaths. Fed up with being bullied by his brother, Hal winds up the toy in hopes of killing Bill, but their mother Lois (Tatiana Maslany) dies instead. Eventually, prompted by the untimely death of Uncle Chip (Oz Perkins himself), the boys toss the toy monkey down a well.

Years later, Hal and Bill are estranged and Hal is divorced with a son, Petey. The cursed toy monkey returns, as these things tend to do, and after a few more zany deaths, it’s revealed that Bill is actually using the monkey to his own nefarious ends. He suspects that Hal tried to kill him with the monkey when they were kids, and he blames Hal for the death of Lois.

Now, Bill is determined to keep winding up the monkey until it kills Hal — but it keeps killing random townspeople instead. Bill tries to force Petey to wind up the monkey, hoping that this will finally make it kill Hal, but Hal refuses to let his son fall victim to the family curse. In Bill’s struggle to control the monkey, he ends up wreaking death and havoc throughout the town. Eventually, Bill gives in and the twins finally have a moment to reconcile — just before the monkey claps its cymbals together one last time, and Bill gets decapitated by a bowling ball with Lois’ name on it.

The movie ends with Hal and Petey driving through the ruins of the now-destructed town. Hal is finally willing to let Petey truly be a part of his family, no matter the baggage, and they’re at peace with their fates as the keepers of the monkey. After the literal embodiment of Death on a Pale Horse passes by and acknowledges them, Hal and Petey decide to go dancing — something Lois used to love.

As you might have guessed from that plot summary, The Monkey isn’t a subtle movie. Yes, it’s an on-the-nose, goofily gory tale of family trauma and grief; but it’s also a deep, uplifting examination of the absurdity of death. In a wonderful interview with Vanity Fair, Oz Perkins described himself as “an expert on losing people in insane ways when [he] was younger.” But instead of letting grief overwhelm him, he chose to explore it through art, and in The Monkey, he ultimately ends that exploration on a hopeful note.

Later in the interview, Oz mentions that he sees Longlegs as a funny movie, too: “If we packed up everything into a time capsule and sent it to Mars to say, ‘This is what humans beings were like,’ the horror genre would have to be included as an example of: ‘This is how we coped. We applied this shit medicinally.’”

As someone who applies this shit medicinally, I couldn’t agree more. In my book, The Blackcoat’s Daughter, Longlegs, and The Monkey represent the perfect array of movies created to cope with grief and generational trauma: from the classically dreadful to the comically absurd, and every scene of Nic Cage scream-singing in a car in between.

Okay fine I'll watch The Monkey again (and maybe I should give Longlegs another shot???)